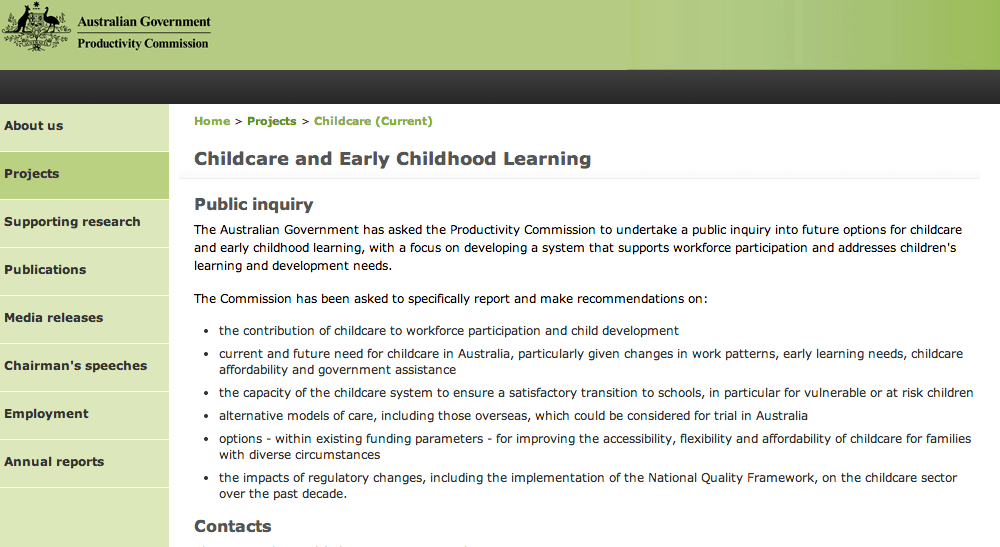

On Sunday November 17, the Federal Government formally launched and announced the terms of reference for the Productivity Commission’s “Inquiry into Child Care and Early Childhood Learning”.

Throughout the Labor Government’s six-year term in office, the Coalition opposition regularly attacked their changes to the early childhood education and care (childcare) sector

Labor convinced all states and territories to sign up, through COAG, to the National Quality Framework (NQF) for early childhood education and care (ECEC). This was a significant achievement, and was an attempt to unify disparate and complicated state-based regulation and oversight.

The principle objectives of the NQF were a concern for the heavyweight players in the ECEC sector, the for-profit private operators. Lower staff-to-child ratios and higher qualification requirements for early childhood educators would directly eat in to their potential profits.

The Coalition gladly took up the banner for the private operators, running ridiculous lines on “the burden of red tape” and “the dead hand of Government regulation”.

For those who take early childhood education seriously, and not as an excuse to make a quick buck, the NQF has drastically streamlined and reduced regulation and paperwork.

This is clearly evident to those of us who managed services in the wildly divergent and complicated system of the National Childcare Accreditation Council, pre-2012.

As promised in the lead up to the 2013 Election, the newly elected Coalition Government will be tasking the Productivity Commission to look into the state of ECEC in Australia. It will report back in October 2014.

Despite assurances from the Government that they support the objectives of the NQF in regards to children’s learning, the Government’s stated intentions in the terms of reference should be ringing major alarm bells for families, educators and early childhood education advocates.

The terms of reference and scope of the inquiry clearly demonstrate that the Government is only viewing the ECEC sector through the very narrow and damaging prism of workforce participation and economic imperatives.

They state it clearly themselves: “We want to ensure that Australia has a system that provides a safe, nurturing environment for children, but which also meets the working needs of families.”

The current Government longs for the days when “daycare” was provided by “nice old ladies” for the love of it.

With the greatest of respect to nice old ladies, those days are over.

Early childhood education and care is about more than a “safe, nurturing environment”. It is a place where children can learn and play socially and safely, developing the skills that will set them up for success in future learning.

Where early childhood education and early learning are mentioned at all in the Government’s announcement, it is far down the list on priorities.

To take a brief look at the section ‘the current and future need for childcare’, “hours parents work” ranks No. 1 on the list.

The “needs of vulnerable or at-risk children”? No. 11.

Could there be a clearer indication of this Government’s priorities?

The Government has also tasked the Productivity Commission to only offer recommendations “within current funding parameters”, effectively ruling out any increase in funding to the sector.

With a sector beset by wages and conditions that should be a national scandal, working with children at the most important stage of their development, this is unacceptable.

The Government’s repeated mantra on “red tape” is also a huge concern. Clear regulation and oversight is essential to the safety and wellbeing of children.

You need only look at systems in the United States and Ireland to see where a desire to not have “unnecessary bureaucracy” has directly endangered the safety, or even the lives, of children.

The inquiry will also be examining the ability of the ECEC sector to meet the “needs of today’s families and today’s economy”.

I am always interested in how it is the community who has to be more “flexible” to business interests.

I’m not sure where the Government’s entreaties to the business community to be more “flexible” to the needs of families are.

Yes, the growing amount of shift and casual work is undoubtedly causing issues for some families (although, as is always the case with this argument, no-one actually has any data to prove it).

But why do we automatically leap to the assumption that the community systems around that issue must change and adapt? Why is there not a national discussion on the business community’s role in supporting families?

The Government’s determination to work within the current market-based system is disappointing, but unsurprising. This was a key “win” for the Howard Government, turning over the education and wellbeing of Australia’s children to profiteering private operators.

The deference to market-based solutions to community and social issues is so stupid as to be hardly worth rebutting.

All that needs to be said is that if the market was capable of providing this “service” to the community in an adequate and cost-effective way, why on earth are there two generous and expensive subsidies available to families (the Child Care Benefit and the Child Care Rebate)?

The inquiry does have the potential to identify systemic issues with the sector, which advocates have been identifying for decades.

Any reasonable examination of the current structure of ECEC can only discover that it is fundamentally flawed. This could be extremely positive for the sector, as the Government can hardly ignore the report it asked for.

The Coalition (and even the Labor Government, who lacked the imagination to fundamentally shake-up the system) have always viewed turning the sector over to the private providers as positive.

It is entirely likely that the Productivity Commission will actually report that it was a huge error that has fundamentally disadvantaged children, families and the community for years.

There will already be a million eyes rolling as they read this, but the fundamental question needs to be asked. Do we want to live in an economy? Or do we want to live in a society?

So ECEC can increase workforce participation. Great. To what end?

This may come as a shock, but I don’t carry out my work as a teacher with children to incrementally increase Australia’s GDP output.

I can think of a number of reasons why ECEC is vital to our community: setting children up to succeed in school and life; lifting children and families out of generational vulnerability; closing the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people.

Preparing children to be good little contributors to the economy is not high up on my list.

Sunday’s announcement needs to be a clarion call to arms for early childhood education advocates. The lines have been drawn.